There is nothing to be known about anything except an initially large, and forever expandable, web of relations to other things. Everything that can serve as a term of relation can be dissolved into another set of relations, and so on for ever. There are, so to speak, relations all the way down, all the way up, and all the way out in every direction: you never reach something which is not just one more nexus of relations. - Richard Rorty

It is perhaps the curse of humanity that we measure one quality against another, on an abstract scale by which we reify concepts and push them around a little so as to get the right and proper weight – or the measurement we prefer.

And really, it’s a natural offshoot of the way we see the world. There is heat, ergo there is cold. Light, darkness. Heaviness, lightness. Life, death. Etcetera etcetera etcetera, as some fictional king of Thailand once said.

It is then not such a long shot that people would, per the transitive effect, start applying it to the fear of death. There is a physical aspect to us, therefore there must be some non-physical aspect as well. This leads to bunny trails all around. Dualism is defined as:

In philosophy of mind, dualism is a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter, which begins with the claim that mental phenomena are, in some respects, non-physical.

Ideas on mind/body dualism originate at least as far back as Zarathushtra. Plato and Aristotle deal with speculations as to the existence of an incorporeal soul that bore the faculties of intelligence and wisdom. They maintained, for different reasons, that people's "intelligence" (a faculty of the mind or soul) could not be identified with, or explained in terms of, their physical body.

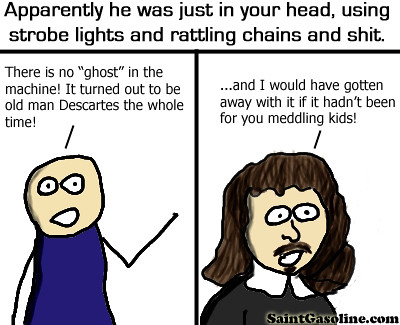

A generally well-known version of dualism is attributed to René Descartes (1641), which holds that the mind is a nonphysical substance. Descartes was the first to clearly identify the mind with consciousness and self-awareness and to distinguish this from the brain, which was the seat of intelligence. Hence, he was the first to formulate the mind-body problem in the form in which it exists today. Dualism is contrasted with various kinds of monism, including physicalism and phenomenalism. Substance dualism is contrasted with all forms of materialism, but property dualism may be considered a form of emergent materialism and thus would only be contrasted with non-emergent materialism. This article discusses the various forms of dualism and the arguments which have been made both for and against this thesis.

Descartes was, as far as I am concerned, a wonderful mathematician but a complete twit philosophically. His prognostications were obviously predicated on presupposition, as the following paragraphs demonstrate:

In his Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes embarked upon a quest in which he called all his previous beliefs into doubt, in order to find out of what he could be certain. In so doing, he discovered that he could doubt whether he had a body (it could be that he was dreaming of it or that it was an illusion created by an evil demon), but he could not doubt whether he had a mind. This gave Descartes his first inkling that the mind and body were different things. The mind, according to Descartes, was a "thinking thing" (lat. res cogitans), and an immaterial substance. This "thing" was the essence of himself, that which doubts, believes, hopes, and thinks. The distinction between mind and body is argued in Meditation VI as follows: I have a clear and distinct idea of myself as a thinking, non-extended thing, and a clear and distinct idea of body as an extended and non-thinking thing. Whatever I can conceive clearly and distinctly, God can so create. So, Descartes argues, the mind, a thinking thing, can exist apart from its extended body. And therefore, the mind is a substance distinct from the body, a substance whose essence is thought.

I don’t know where to start in on this. 1. he obviously didn’t call all his prior beliefs into question, because obviously he was a theist throughout the entirety of this ‘meditation’, 2. he didn’t apply the ‘brain in the vat’ very rigorously, 3. he obviously didn’t conceive of the possibility that the brain couldn’t operate independently of the body…the list goes on.

The central claim of what is often called Cartesian dualism, in honour of Descartes, is that the immaterial mind and the material body, while being ontologically distinct substances, causally interact. This is an idea which continues to feature prominently in many non-European philosophies. Mental events cause physical events, and vice-versa. But this leads to a substantial problem for Cartesian dualism: How can an immaterial mind cause anything in a material body, and vice-versa? This has often been called the "problem of interactionism".

Gee thanks, Renee. You managed to wreck Western civilization with an expression of your solipsism. Nice going.

Descartes himself struggled to come up with a feasible answer to this problem. In his letter to Elisabeth of Bohemia, Princess Palatine, he suggested that animal spirits interacted with the body through the pineal gland, a small gland in the centre of the brain, between the two hemispheres. The term "Cartesian dualism" is also often associated with this more specific notion of causal interaction through the pineal gland. However, this explanation was not satisfactory: how can an immaterial mind interact with the physical pineal gland? Because Descartes' was such a difficult theory to defend, some of his disciples, such as Arnold Geulincx and Nicholas Malebranche, proposed a different explanation: That all mind-body interactions required the direct intervention of God. According to these philosophers, the appropriate states of mind and body were only the occasions for such intervention, not real causes. These occasionalists maintained the strong thesis that all causation was directly dependent on God, instead of holding that all causation was natural except for that between mind and body.

Geez, does any of that sound slightly familiar?

The more recent argument is that thoughts/consciousness/mentality are composed of energy – therefore they can exist independently of the mind. Of course, when anyone points out that that is unprovable…well, the current response is not only a fallacy, but negligible: “You can’t prove otherwise!” (And we all know how that conversation ends.)

Now here in modern times, we can stipulate without hesitation that the mind and body are not ‘separate and distinct qualities’; we can deduce via induction that the mind cannot function without the body attached (as of this writing, science fiction hypotheses notwithstanding), and we can safely theorize that culled information doesn’t survive the destruction of the body as some ephemeral wisp haunting the nights or the clouds or the molten center of the earth. In fact, it is safe to say that for the most part, all those philosophers and alchemists and necromancers and ‘spiritual geniuses’ were for the most part, full of it.

And that’s my nickel’s worth.

Till the next post, then.

No comments:

Post a Comment